In the spring of 1993, I was 12 years old when a sudden illness swept through my family. It started with a subtle discomfort in my stomach, but within days, it escalated into a sickness that left us bedridden for over a week. Our entire neighborhood seemed to be ill.

Unknown to us, our proximity to the Howard Water Treatment Facility, one of Milwaukee's primary water treatment plants, was the source of our suffering. The news broke too late, revealing that the water flowing from this facility was contaminated with Cryptosporidium, resulting in an “Estimated 403,000 people falling ill” (The New England Journal of Medicine, 1994). Due to this experience, I know firsthand the importance of ensuring clean water is supplied throughout our nation’s distribution networks.

To learn more about this outbreak in Milwaukee, click here to be redirected to an interactive presentation.

A REAL-WORLD SCENARIO - WHAT WOULD YOU DO?

I recently heard about a contractor hired to install a new waterline to improve the water supply infrastructure in a growing residential area. The project involved laying a 12-inch diameter Ductile iron water main over two thousand feet as the main water supply to the new residential development.

Upon completion of the installation, the standard procedure requires a Bacteriological Test (Bac-T test) to ensure that the new waterline is free from bacterial contamination before it is put into service. The Bac-T test results for this new waterline returned positive for coliform bacteria, indicating contamination in the newly installed waterline. This is a serious issue, as bacterial contamination in drinking water can lead to severe health risks. As a result, the utility instructed the contractor to remove and reinstall a new pipeline, which is very unusual. Was it even necessary?

In this #IronStrong Blog, we'll examine the reasons behind these failures, explore the steps to take when faced with a failed Bac-T test, and, most importantly, discuss actionable strategies for remediation and prevention.

WHAT IS A BACTERIOLOGICAL TEST (BAC-T TEST), AND WHERE DID IT ORIGINATE?

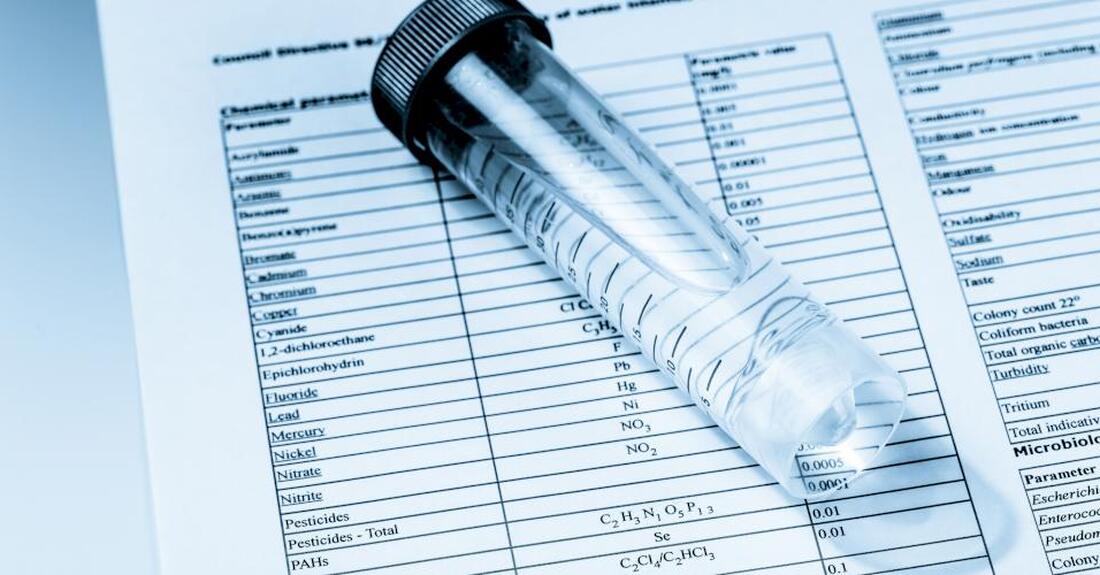

According to epa.gov: The Total Coliform Rule (TCR), a National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR), was published in 1989 and became effective in 1990. The rule set both a health goal (Maximum Contaminant Level Goal (MCLG)) and legal limits (Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs)) for the presence of total coliforms in drinking water.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set the MCLG for total coliforms at zero because there have been waterborne disease outbreaks in which researchers found very low levels of coliforms. The MCL levels are based on the positive sample tests for total coliforms (monthly MCL), total coliforms and Escherichia coli (E. coli), or fecal coliforms (acute MCL).

The purpose of the 1989 TCR is to protect public health by ensuring the integrity of the drinking water distribution system and monitoring for the presence of microbial contamination.

This new rule was updated to the Revised Total Coliform Rule (RTCR) in 2013 and required full compliance starting April 1, 2016. The Bac-T test is required to demonstrate that a pipeline under construction or exposed to the surrounding environment through a failure has been disinfected from waterborne before it can be connected to the existing system. This prevents isolated contaminants from being released into the entire water system.

HOW CAN WATERLINES GET CONTAMINATED?

No matter what type of waterline is used, here are the primary ways waterlines become contaminated before they are put into :

- Transportation Issues: During transportation, pipes might become contaminated through contact with surfaces, other materials, or exhaust fumes.

- Unclean Tools: Tools and equipment used during installation can introduce bacteria into the waterline.

- Contaminated Hands or Gloves: Workers handling pipes with contaminated hands or gloves can transfer bacteria onto the pipe surfaces.

- Soil and Water Exposure: Pipes encounter soil or non-potable water during installation and pressure testing.

- Animal Intrusion: Animals or insects might contact the pipes during storage or installation, introducing contaminants.

One of the most common methods of ensuring that a new or existing water line is free of microbial contamination is to introduce Calcium Hypochlorite. When used properly, this inorganic compound destroys germs that can lead to various health problems. But to keep our readers on topic, I will discuss the “how-to” from a post-failure perspective. You can also check out this very informative blog by my colleague Bob Hartzel, which details Calcium Hypochlorite and provides step-by-step instructions on its use: What is the Purpose of Calcium Hypochlorite Granules?

WHAT TO DO IF YOUR BAC-T TEST FAILS?

Let’s say a test comes back positive for coliforms; now what? If the Bacterial Test fails after installing a new waterline, it's crucial to take immediate action to address the issue. You can save time and further expenses by performing the procedures listed below.

1. Conduct a Root Cause Analysis: Investigate how the contamination occurred. Review storage, handling, installation, and testing procedures to identify potential contamination points.

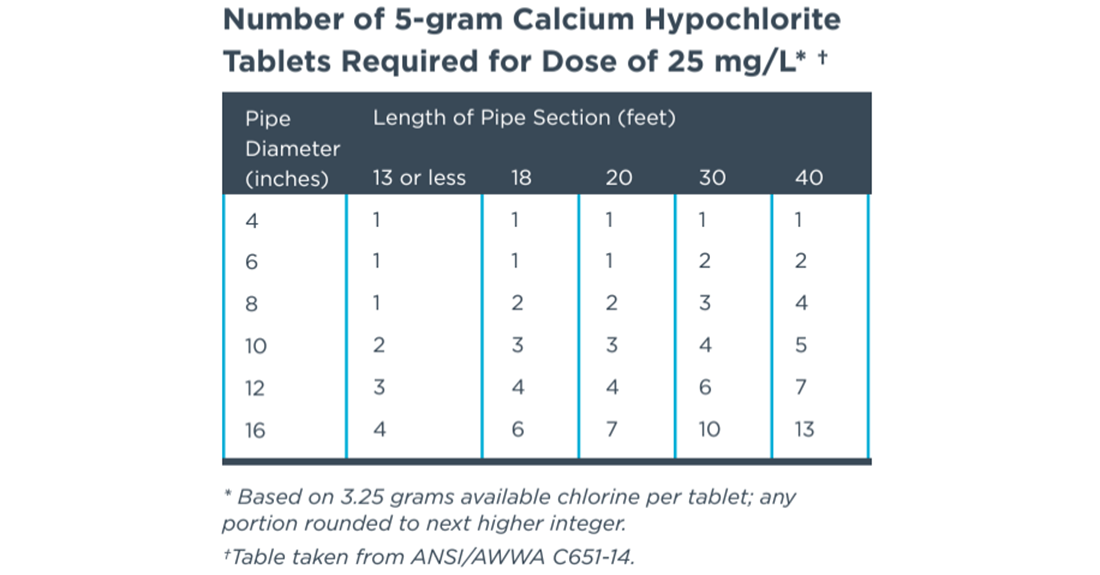

2. Clean and Disinfect: Flush and disinfect the contaminated section of the waterline. Increase the chlorine solution from 25 mg/L to 50 mg/L and proceed according to ANSI/AWWA 651 standards. McWane Ductile has a great blog post on this procedure, which can be found here.

3. Re-flushing: After disinfection, thoroughly flush the waterline with potable water to remove any remaining disinfectant and debris.

4. Conduct Additional Bac-T Tests: After disinfection and flushing, conduct another series of tests to ensure the contamination has been entirely eradicated. Multiple samples may be required to confirm the water is safe. Ensure that the sample area has been thoroughly sprayed with alcohol to ensure your sample is not contaminated outside the pipeline.

MY BAC-T TEST FAILED FOR THE SECOND TIME. NOW WHAT?

What if you retested your waterline and failed the Bac-T test a second time; now what? First, understand this is somewhat common. When you fail a test for a second time, the following steps are typically involved in addressing contamination, ensuring the waterline is safe, and preventing similar problems:

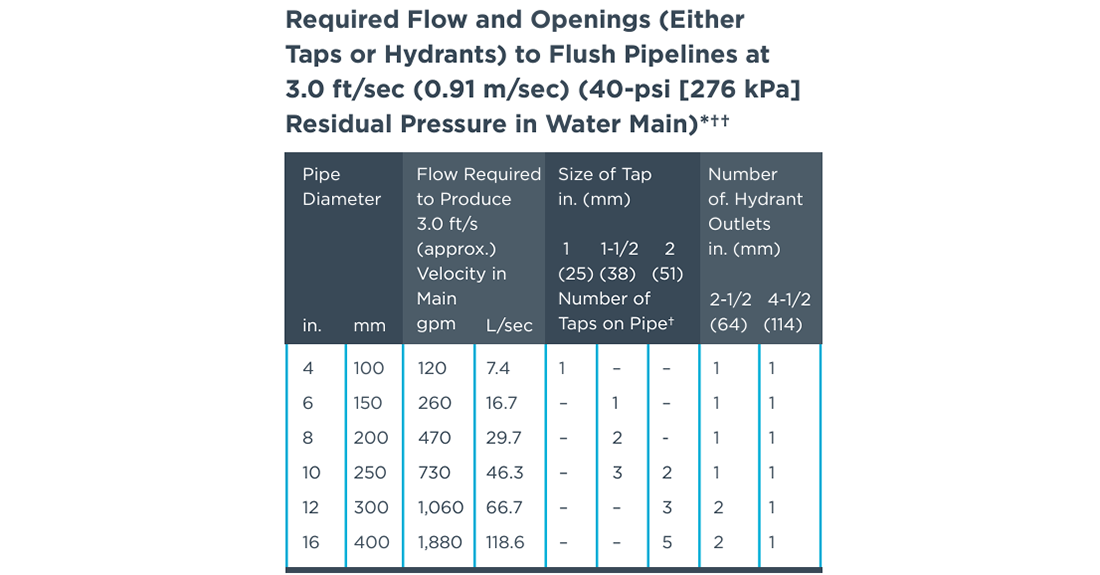

1. Flushing the Line: Flush the waterline at a high velocity to remove debris and loose contamination. Also, ensure all parts of the waterline are flushed, especially dead ends and low-flow areas.

2. Disinfection: A slow-flowing slug of water, chlorinated to at least 100 mg/L free chlorine, is introduced into the main. The slow flow rate shall ensure that all parts of the main are exposed to the highly chlorinated water for at least 3 hours. If the free chlorine residual drops below 50 mg/L, the flow should be stopped, and the procedure should be restarted at that location with the free chlorine restored to at least 100 mg/L.

3. Post-Disinfection Flushing: After the contact time has elapsed, flush the line again to remove the disinfectant. Use potable water to flush until chlorine residual levels reach acceptable limits (e.g., below 4 mg/L for free chlorine).

4. Retesting for Bac-T: Collect water samples from multiple points along the waterline. Submit the samples to an accredited laboratory for Bac-T testing. Ensure all samples return negative results for coliform bacteria before considering the line safe for service.

YOU CAN ENSURE YOUR WATERLINE IS SAFE AND HEALTHY

In this blog, we discussed the steps to take when dealing with a failed Bac-T test or multiple failed tests. We also explored the root causes of failures and explained actionable remediation strategies. It's essential to provide clean, safe, and disease-free water. All waterlines must meet standards to deliver secure, reliable, and affordable water to end consumers. If a waterline fails a Bac-T test, replacing it with a new one is unnecessary and excessive. Following these strategies will ensure that your drinking water distribution systems are free from microbial contamination.

NEED ASSISTANCE WITH YOUR WATERWORKS PROJECT?

If you have any questions regarding your water or wastewater infrastructure project, your local McWane Ductile representative is equipped with the expertise to assist you. Many of our team members have managed small and large water utility systems, served in engineering consulting firms, and bring decades of experience solving field issues involving pipeline construction and operation. From design to submittal to installation, we strive to educate and assist water professionals throughout the water and wastewater industry.

REFERENCES

- New England Medical Journal, "A Massive Outbreak in Milwaukee of Cryptosporidium Infection Transmitted Through the Public Water Supply." William R. Mac Kenzie, Neil J. Hoxie, Mary E. Proctor, M. Stephen Gradus, Kathleen A. Blair, Dan E. Peterson, James J. Kazmierczak, David G. Addiss, Kim R. Fox, Joan B. Rose, and Jeffrey P. Davis. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199407213310304, VOL. 331 NO. 3 (July 21, 1994): 161-167, 331.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. “Revised Total Coliform Rule and Total Coliform Rule.” Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo/revised-total-coliform-rule-and-total-coliform-rule#rule-history

- Water Well Journal, Thumbley, Thad. “The Mysterious “Bac-T” Test.” Accessed May 1, 2024. https://waterwelljournal.com/the-mysterious-bac-t-test

- Ductile Iron Pipe Research Association. “Installation Guide for Ductile Iron Pipe.” Accessed May 1, 2024. https://dipra.org/docs/ductile-iron-pipe-installation-guide-english